SKIJORING'S WILD HISTORY

Getting dragged across the snow by horses, planes, reindeer and dogs is a unique sport that's at least 1,000 years old.

By Jay Cowan

Skijoring, one of skiing's oldest activities, has be come one of the latest feel-good winter sports. If you’re doing the popular dog-powered variation-whether pulled around a cross-country track by your own fleet of Corgis, or using huskies supplied by an outfitter-you're enjoying a recreation that dates back at least 1,000 years.

The term "skijoring" comes from the Norwegian snorekjoring and means "ski driving." Rock art in Scandinavia shows humans skiing as early as the 5th century AD. Later, there are depictions of skiers being pulled by elk (likely while being captured) and reindeer, possibly domesticated. The first written record of what we define as skijoring comes from the Altai Mountains of central Asia, via a Persian historian, Raschid ed-Din. He wrote in the 1200s AD, citing earlier use of skijoring from historical records of the Tang Dynasty (618 to 907 AD).

In The Culture and Sport of Skiing: Antiquity to WWII, historian E. John B. Allen notes that there are numerous references in literature over the years, starting in 1878, to the Persian account. Allen also studied translations of a 1993 book, A History of Chinese Skiing, edited by Zhang Caizhen, which reports that during the Yuan and Ming dynasties, starting in 79 AD, " ... tens of dogs pull a person on a pair of wooden boards ... galloping on the same snow and ice faster than a horse."

Skijoring likely arose spontaneously in various parts of the world as people adopted the idea of skiing in general. The canine version mentioned in China has also long been popular in Sweden, where skijoring has been closely connected to pulka, which involves sleds being pulled by dogs. In Lapland and Siberia, reindeer have been the animal of choice for pulling sleighs and skiers. And A History of Chinese Skiing also refers to horses being used in the Altai during the Yuan/Ming era.

While skijoring started as a mode of transportation, racing introduced a competitive side to the sport. Informal competitions had doubtless been held for years, but the first time skijoring showed up as a recorded sport at a major venue seems to have been in the Stockholm Nordic Games of 1901, where it was the reindeer version. Similar events are still held today in Norway, Finland and Russia.

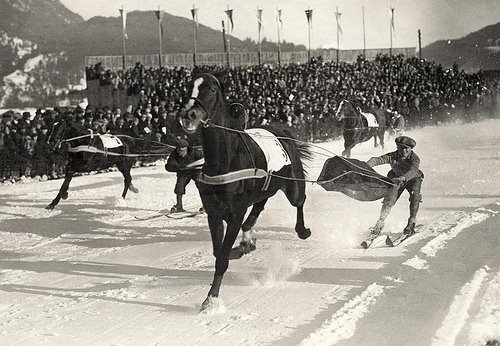

By 1912 in the Alps and Poland's Tarra Mountains, equine skijoring was all the rage. In 1926 the Chamonix International Sports Week included it, and it was a demonstration sport at the 1928 Winter Olympics in St. Moritz.

The St. Moritz style features multiple teams racing around an oval track. The skier travels directly behind the riderless horse, teth- ered by reins that steer the animal. It's an exciting event, with chaotic conditions and impressive skills required to handle the skiing, the steering, and the stampeding traffic.

The equine version that surfaced in America came from Scandinavia in a slightly different form. A rider was installed on the horse, the ropes pulling the skiers got longer, and most of the tracks were straight and contained gates or jumps for the skiers. This new North American winter pastime seemed to appear almost simultaneously in 1915-1916 in Lake Placid, New York, the Dartmouth Winter Carnival in Hanover, New Hampshire, and the annual Steamboat Springs Winter Carnival in Colorado, where it has been featured continuously every since.

Just in case skijoring behind hard-charging horses wasn't sporty enough, the sport went motorized in the early 1900s. John Allen's book includes a drawing of Norwegians behind motorcycles in 1906, photos of the French doing the same in 1914, followed by the Swiss in 1929 and the Russians in 1931. Swiss and Canadians used airplanes in the 1920s. Famous footage shows motorcycles and sports cars towing skiers in Bavaria at speeds upwards of 100 mph. (To see a clip from 1955, go to www.britishpathe.com and search for a video titled "The World's Most Dangerous Sport.")

The military applications of skijoring came into full play in WWII, whether in the Apennines of Italy with the 10th Mountain Division, or in Norway where resistance soldiers used reindeer to pull skiers and supply sleds. The U.S. Army has released photos of current day mountain troops skijoring behind large, military-grade snow machines.

More than a dozen countries and numerous states are now hosting races. In 2019, eight events were scheduled in Colorado, Wyoming, Idaho and across Montana under the auspices of Skijoring America, with numerous other independent events on tap across the country.

What attracts competitors isn't just the thrill, but increasingly hefty purses that top $20,000. At this year's Best in the West Showdown in Big Sky, Montana, top teams in multiple disciplines walked away with as much as $2,000 and rodeostyle belt buckles. Likewise, what appeals to spectators isn't just the novelty and action but the frequent side betting. With the Calcuttas-an auction in which participants bid on contestants-there's often enough money involved to make for a profitable weekend all around.

The unique Arctic Man event in Alaska, which started as a bar bet in 1985, combines regular ski racing with snowmobile ski- and board-joring over a 5 mile course with a record speed of 91.6 mph. With 13,000 spectators, the AM has seemed like a far north XGames. Speaking of which, it seems only a matter of time before snowmobile skijoring debuts at an XGames somewhere, and one of skiing's oldest competitions will merge with one of its newest.

Jay Cowan is a frequent contributor to Skiing History who divides his time between Montana and Aspen.

VOLUME 31, NO. 2 MARCH-APRIL 2019